Black Dolls: Play, Resistance, and Determination

In the face of racism, ethnic dolls demand authenticity and place

You are too old for a doll.

But she’s so pretty.

You’re grown–with kids!

But she’s so pretty.

In the toy aisle, I stare at the dark-toned, brown-eyed doll smiling back at me, her lips plump and full.

Growing up, all the dolls I’d had were blonde and blue-eyed. The only Barbie I would own was the Malibu one, the blondest and bluest-eyed at that time. If Black dolls existed in Las Cruces, New Mexico, I didn’t know about it. The shelves at Toys by Roy and TG&Y offered white doll after white doll.

I hesitate only a little longer before ending the mental debate. I snatch up the box the doll is packaged in, and rush to a register. I want to get home so I can play with my new doll.

***

Doll historian Debbie Behan Garrett understands.

Author of “The Definitive Guide to Collecting Black Dolls,” she maintains a website DeeBeeGee’s Virtual Black Doll Museum, two blogs Black Doll Collecting Blog and Ebony-Essence of Dolls in Black, as well as Pinterest pages about the same.

“Through Black dolls, I celebrate positive images of Black people. Dolls that are true depictions of the people they portray bring me joy,” Garrett says. “Owning Black dolls as an adult fills the void of not owning them as a child.”

Political activist Marcus Garvey had advised women to buy a certain doll for their children. “Mothers give your children dolls that look like them to play with and cuddle. They will learn as they grow older to love and care for their own children and not neglect them,” he’s been quoted as saying.

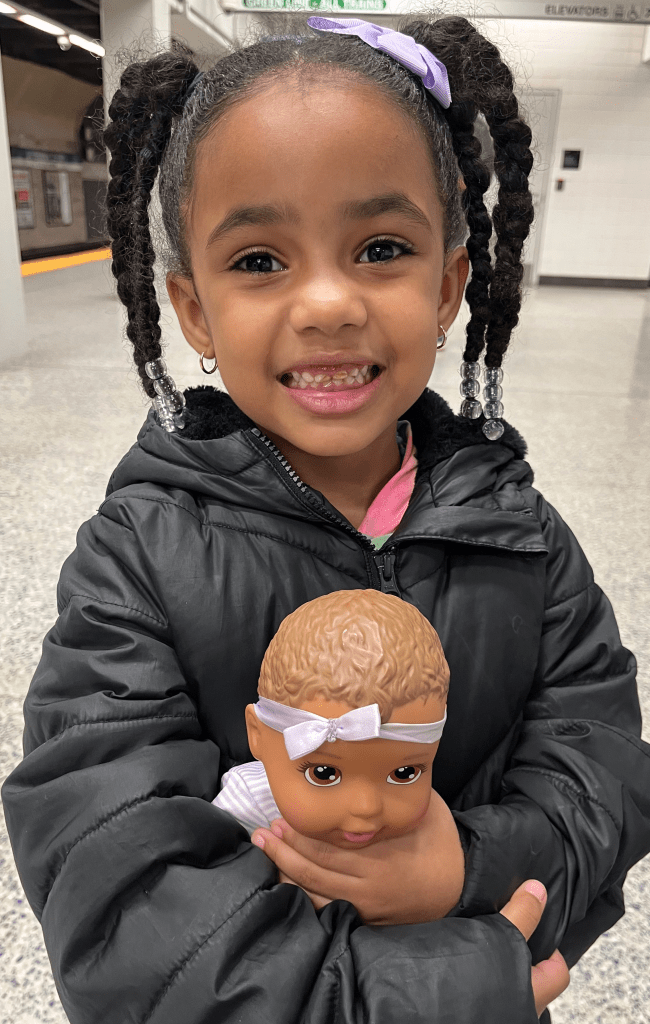

Four-year-old Aniyah with one of her five Black dolls.

Angela Mitchell-Williams, growing up in Panama, was fortunate to have a Black doll.

But for many Black mothers, Black dolls for their children were elusive.

Vanessa Loud, of Roxbury, Massachusetts, remembers no Black dolls being sold in the Woolworth where her mother shopped. “My mother just didn’t know how to get her hands on them,” she says. Black dolls would arrive when a store called Nubian Notions made its way to that part of Boston, bringing with it all things Afrocentric, including dolls. But by then Loud was no longer playing with them.

Growing up on the island country of Jamaica, Christine Roberts says there, too, were only white dolls. Roberts now lives in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Chatting with her in the toy aisle of a retail store, she explains that when she had a daughter, she chose to not buy her dolls until a particular time.

“I waited until she understood colors, then I bought her Black dolls,” Roberts says.

The now-10-year-old daughter and Roberts’ 6-year-old niece express their preference for dolls that have a skin tone similar to their own; the daughter with a Black LOL tween doll in hand, trying to convince her mother to buy it.

Debra Britt, of Mansfield, Massachusetts had a grandmother who would dye her white dolls Black so that Britt would “understand who she was.”

Britt is the executive director of the National Black Doll Museum of History & Culture.

Black dolls “were very rare” when Marva Nathan was growing up in Virginia. She says there were people who made them, but Black dolls were not available in the markets. She is happy her grandchildren get to enjoy play with Black dolls.

Black dolls are now much easier to find for purchase. Major toy manufacturers have been adding Black dolls to their toy lines for decades. A 1991 copy of “Marketing News” highlighted that Hasbro, Tyco, and Mattel’s interest in “dolls designed specifically for the Black market” was due to demographics. A bit more economics involved than cultural evolution. Businesses go where the money is.

But Black people already been knew. There was always a market for ethnic dolls that were authentic.

The real progress is the number of Black-owned businesses creating and selling them today.

Retailer Target has partnered with several Black-owned toy companies. You can find dolls from HarperIman, Fresh Dolls, Naturalistas, Positively Perfect, Orijin Bees, HBCyoU, Ikuzi Dolls, Surprise Powerz, Our Generation, Healthy Roots, and Our Brown Boy Joy on their website and/or in their stores.

Black dolls can be found online at Step Stitches, Corage Dolls, Trinity Designs, Pretty Brown Girls, and Herstory Doll. And, of course, there’s Amazon where Qai Qai, a replica of Serena Williams’ daughter’s favorite doll is sold. Qai Qai can also be found at The Black Toy Store.

Our Brown Boy Joy hopes to inspire and empower young boys. Twenty-five-year-old Kelson John, of Boston, would have appreciated that had such a company been around when he was a boy. He has two nieces who play with Black dolls because his sister thinks it’s important, but he recalls having only one Black male toy figure as a boy–a wrestling character within a set of white ones.

The dolls at HBCyoU celebrate Historical Black colleges and Universities. Through dolls, Trinity Designs honors the Divine Nine, Black sororities and fraternities which were created–like the Historically Black Colleges and Universities–because Black people were excluded.

Healthy Roots Dolls focuses on “educational play experience with curl care.” The company offers Zoe, Marisol, and Gaiana–“curlfriends”–dolls with hair that can be styled a multitude of ways, from Bantu knots to box braids, to help girls of color learn to love their hair.

The common mission of these Black companies is creating dolls that not only promote diversity in play but also honor the blackness of little girls and boys.

Dr. Lisa Williams. CEO of World of EPI, says, “I want all children of all ethnicities to see authentic dolls that reflect their beauty and brilliance, especially Black little girls who were my inspiration in starting this company.”

World of EPI stands for Entertainment, Publishing, and Inspiration. Fresh Dolls, Positively Perfect, Simply Fresh, and Fresh Squad Doll Collections fall under the umbrella of the company.

Marvel/Disney selected World of EPI to create the tie-in dolls for the movie Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. The Fresh Dolls Fierce collection went on to win the Toy of the Year Award in 2022.

Williams did not play with dolls, Black or white, growing up. She preferred books. Still, she remembers her sister having Black dolls, though they looked like a white doll “simply painted brown.”

She left a high-ranking academic career to form EPI as a way “of spreading joy by providing children with dolls that inspire dreams, promote intelligence, and build self-esteem.” Creating dolls is a “mission of love” and authenticity is key, she says.

“Dolls need to be relatable. My goal is that when anyone picks up one of our dolls, they’re able to connect with it. . . I feel as though the more a doll looks like the child or others in the child’s life, the more intimate the child/doll relationship,” Williams states.

Those would be dolls that mirror Black folks in their full spectrum of skin tones.

Hair that is coiled, curled, or spiraled. Braids and ‘fros.

Loud confesses she was so struck by the straight hair on a white doll that she wanted to alter her own to match. Her mother, who was a hairdresser, discouraged her.

“She was trying to teach me something I wasn’t aware of yet,” Loud says. “I didn’t understand why she was so adamant, but she knew how Black women tussled with their hair and she wanted me to like myself as I am. My nappy hair was my beauty.”

It’s not just for cultural reasons that dolls that are ethnically correct matter to Black people. It’s political, too. Authentic-looking dolls are the physical representations of Black beings’ right to be as they are. Not some gross misrepresentations of a race.

***

I love all of history, the good and what we don’t want to talk about. In Tennessee, I was taking a tour of a plantation. The Black cloth doll on the dresser in the white baby’s nursery room surprised me. I played with white dolls growing up, but did white children play with Black dolls?

Well, yes.

And, no.

That particular Black doll in the nursery was not a toy, the tour guide told me when I asked about it. Providing a Black face to soothe a distraught child if the slave who cared for it was unavailable was that doll’s sole purpose.

***

Black people and the United States have a history. Even in play and it goes deep.

Today, a puzzle issued by the McLoughlin Brothers called “Chopped Up N-words” would have a hard time finding space on a shelf in a toy section of a retail store.

Today, a doll from the Butler Brothers would not be described in advertising as a “glazed n-word baby.”

Today a wind-up toy called Dapper Dan Coon Jigger, well, just couldn’t be called that.

But a century or so ago, it was different.

So, back to the ‘yes’ from up above: White children played with Black dolls. But there were two markets in the time between the late 19th century and the early 20th one, according to anthropologist Anthony Martin. Black and white children were offered Black dolls which had been “made from white doll molds,” he says.

Black dolls marketed exclusively to white children had another purpose. A job to fulfill.

Racism and classism were “perpetuated” by way of playthings based on racial stereotypes; these toys serving as the “visible template” for white children, Martin writes. From his research, he has found “no less than 237 Black racialized dolls on the market between 1850 and 1940.” Advertising at that time, he discovered, described the dolls as “n-word, pickaninny, darkie, dusky or Mammy.” And that included catalogs from companies such as Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward.

It was one of my greatest joys growing up to circle all the things I wanted but was not going to get in the Sears Roebuck Christmas Wish catalog. Pretty upsetting to find this historical tidbit out about my favorite catalog and of that of a favorite store.

Another idea perpetuated by such dolls was the continued commitment to violence against Black bodies. Robin Bernstein’s research about dolls in the 19th century reveals that white children could love (I’m air-quoting that word) their Black dolls while acting viciously toward them. Bernstein writes in “Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights,” about a child whose mother claimed she was quite affectionate toward her “colored doll,” yet the child was still able to cut its throat. “Love and violence,” Bernstein says, “were not mutually exclusive. . . even as historical white children loved their Black dolls , they whipped, beat and hanged Black dolls with regularity. . .”

In Worchester, Massachusetts, in 1897, white children were seen conducting slave auctions and burning their Black dolls.

There are white children today who behave the same way, though without the proclaimed love.

Bernstein also writes that doll makers encouraged the violence. In Massachusetts–again–a company advertised a Black doll. The promotion asked “What child in America does not at some time want a cloth ‘N-word’ dollie – one that can be petted or thrown about without harm to the doll or anything that it comes in contact with… ‘Pickaninny’ fills all the requirements.”

Even recently, a Black rag doll you could abuse to make yourself feel better was being sold. Yes, there were other colors that were made but neither could be assigned to a race of people.

Many of the 19th century dolls sold exclusively to white children were servant dolls, which came to be known as the “Mammy” doll.

The dolls, like other toys at the time, “centered on an antebellum theme,” Martin says, with the purpose of “shaping African Americans as ‘the other’ and inferior to whites.” He adds that the stereotypes are the manner in which the dominant culture uses caricature to define African Americans,

Garrett says, “Mammy dolls and other caricatures that depict them are part of American history, usually made by non-Black people to portray enslaved Black women as happy with their lots in life to cook, clean, nurse and otherwise care for children, and serve in households of white people.”

She adds that the depiction of Black women’s disposition through such dolls is not true to the women doing what they had to do to survive.

Garrett says that those who hold onto the caricature of the mammy doll have their consciences eased by the doll concept and merchandising.

“I have the utmost respect for formerly enslaved women who were household and family caretakers for enslavers and for those in the post-enslavement period who performed day work in other people’s households for a pittance,” Garret says. “Depicting them as happy, wide-grinning, obese women is inaccurate, insulting, and not true Black history.”

Another racist doll popular in England, the American South, and Australia was the golliwog. Its popularity has waned in recent years. But the golliwog with its jet-black skin, grinning red lips, wild hair and bulging eyes, has its defenders.

The doll is not racist, they say.

For years, English jam company James Robertson & Son used the golliwog image for branding. People could collect tokens from their jams that could be traded for badges. Golliwogs, because no trademark was originally sought by Florence Kate Upton who created the character, appeared on a variety of items, including powder boxes. Its head sat atop perfume bottles. You could buy golliwogs as porcelain figurines or salt and pepper shakers. For many white people, the familiarity of the rag doll holds sentimental meaning. However:

The rag doll was based on characters in a minstrel show.

Minstrel shows were racist by design.

Does not 1 + 1 = 2?

Martin says the British origin story is why the doll continues to be sold today.

In 2009, the Queen’s gift shop was selling golliwogs, which were later removed, with an apology from Buckingham Palace. In early April 2023, The Guardian carried a story about the British police raiding a pub and taking the golliwogs displayed there. The British Crime and Disorder Act 1998 prohibits behavior that is “racially aggravated.”

One of the pub’s owners had posted a picture of the golliwogs on social media when the bar first received them. The dolls hung by rope from shelves. In the comment section, he’d written “They used to hang them in Mississippi years ago.” The owners deny being racist.

1+1 is still equaling 2.

Garrett views golliwogs as “a negative, insulting, stereotypical portrayal of Black men.”

She says golliwogs are not the “warm and fuzzy characters. . . collectors imagine them to be.”

Sometimes collectors experience a dilemma. They don’t want to throw the dolls away, but they can’t keep them because to do so would make one appear racist. To resolve it, some send their golliwogs to Britt for her doll museum and she keeps them because, she says, they provide a teachable moment with others.

***

In his article about racialized dolls, Martin writes about a time when “African Americans were advocating for another wave of racial pride and uplift within Black communities.” In the context of Black dolls, his words could apply to any time, every time, Black people (and some white people as well) worked to create positive play in the life of Black children.

Evidence submitted to the Supreme Court during the 1954 landmark case Brown vs. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas explains why.

There were two dolls, identical but for their color. One was white, the other Black.

Social psychologist Kenneth Clark asked the children to “give me the doll that is a nice color,” “give me the doll that you would like to play with or like best,” “give me the doll that looks bad” among other questions for a total of eight. The questions were to determine a child’s knowledge of racial difference and to show if they had a racial preference.

They did. For positive attributes, they did not prefer the Black doll.

That pretty much remains still today. Television news programs on ABC and CNN have revisited the test, with ABC having slightly different results, but CNN seeing similar.

Educator Dr. Toni Sturdivant recreated the doll test with exclusively Black girls. The children Sturdivant studied were “mono-racial Black,” the school the children attended was run by someone who was Black, the teachers in the classroom were Black, and the majority of the class was Black.

The children did not prefer the Black doll.

The Clark doll test looked at the effects of segregation and how it affected how Black children saw themselves; today the emphasis is on the anti-Blackness prevalent in society.

“We see these results due to the pervasiveness of anti-Black rhetoric that is experienced by all and has the potential to be internalized by anyone regardless of their race or ethnicity,” Sturdivant says.

Countering anti-Blackness is surely a good fight, and when it comes to dolls, one Blacks folks have been fighting and fight still today.

***

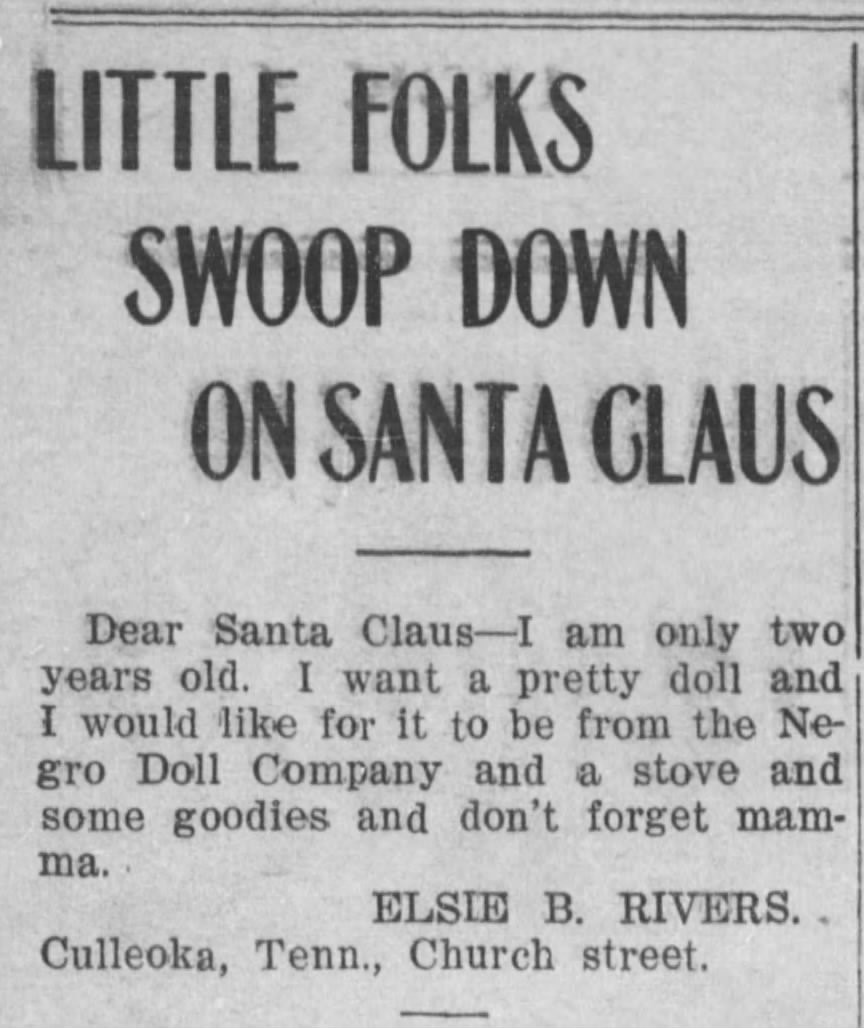

In creating the first Black-owned doll company, Richard Henry Boyd sought to give an “opportunity. . . to every Negro family to secure a beautiful Negro doll for their girls.” It was located in Nashville.

Boyd could not find dolls for his children which were not exaggerated misrepresentations. His feelings about this were expressed in an ad which stated that “Little Negro girls” should be encouraged to “clasp in their arms pretty copies of themselves.”

A former slave and self-educated businessman, Boyd got a German manufacturer to make dolls, adopting a process that used unglazed porcelain so a darker tone could be had. In August of 1908, the dolls were advertised for sale in the Nashville Globe. Boyd created the Negro Doll Company to handle the number of sales. As knowledge of the dolls spread across the U.S., so did the orders. The business name changed to the National Negro Doll Company to reflect the scope of its consumers.

Booker T. Washington had recognized the work the company was doing. “…Colored people have begun to see the wisdom of giving their children dolls that have their own color and features, and which will have the effect of instilling in Negro girls and in Negro women a feeling of respect for their own race,” he said.

In 1911, Boyd moved the manufacturing of the dolls to Nashville. By 1915, the business had ceased.

A short article in a 1920 copy of the Black newspaper The New York Age announced that Berry & Ross had “launched the first Negro venture in large scale manufacture in Harlem.” The making of “brown-skinned dolls,” the article said was “practically unthought of, or at least not attempted before in Harlem.”

Evelyn Berry and Victoria Ross established their factory at 36-38 W. 135th Street in 1918. They sold clothing in addition to dolls. By 1921, a branch had been established in Virginia, a retail store had been opened on 65 W. 135th Street, and their “colored dolls” were making their way across the ocean to West Africa.

Creating racial pride was a mentioned goal of Berry & Ross. That, and their dolls being in 12 million Negro homes. Both boy and girl dolls were offered. You could order a girl doll with hair that was wavy, straight or set in a Marcel curl. Boy dolls came dressed in a romper or in full soldier uniform.

Marcus Garvey had created the Universal Negro Improvement Association, with The Negro Factories Corporation a part of the organization to promote financial independence for Black people. Michele Mitchell writes in the book “Righteous Propagation: African Americans and the Politics of Racial Destiny after Reconstruction” that in 1922, Garvey’s organization “acquired” Berry & Ross and began making the Black dolls he had been promoting though his newspaper, Negro World.

However, there is uncertainty if this is the case as there are conflicting dates of operation. One article claims Berry & Ross operated through 1929. The Negro Factories, in some reports, is said to have been dissolved in 1921; another saying the mid -1920s.

Sara Lee was another attempt at the mass production of a Negro doll. She had the backing of Eleanor Roosevelt, Ralph Bunche, Zora Neale Hurston and other prominent people. Unfortunately, the doll did not have the unanimous backing of the executives of Ideal Toy Company, the biggest U.S. toy maker at that time, who had agreed to manufacture and distribute the doll.

Sara Lee Creech, a white woman, had seen two Black girls playing with white dolls. Involved in both interracial and women’s causes, she felt it was wrong and enlisted people she knew to set out to create an “anthropologically correct” doll for Black children.

Expectations for Sara Lee (the doll) were high. Better Homes and Gardens wrote “New Negro doll is designed to replace the ‘Mammy’ dolls of the past.” She was going to be “the ultimate Negro doll.” For white children, she would be an “ambassador of peace.” An ad hailed her creation as a “real step forward in the field of race relations.” Ebony magazine anticipated her success.

Because Black people have skin in a variety of colors, the inability to create Sara Lee with a skin tone that would be acceptable to many came to be known as the “color issue.” What tone was the color that would “validate” the Black race? The proposed solution would be a family of dolls; each which would have a different skin tone as well as hair type. But they would never be.

Early sales of Sara Lee were encouraging but the commercial success hoped for never came. The color issue identified in the production stages remained an issue. Once in stores, Black customers found the doll unrepresentative of the darker-hued members of the race. White customers thought her either too light or too dark.

Additionally, the materials used to create the doll would harden, the dye seeped into the doll’s clothes, and the skin color changed. Gordon Patterson says some Ideal executives came to see Sara Lee as a “marketing gimmick” and, in 1952, decided to not expand to a family line. By 1953, production of the doll had ended.

On February 20, 1949, Amosandra, the third child of Amos and Ruby from the Amos ‘n Andy show was introduced on the radio broadcast. A week later a doll commemorating the event arrived in stores.

The idea to make the doll was that of Sun Rubber Company’s general manager Thomas W. Smith Jr. According to an article in the Akron Beacon Journal, the company had been “bombarded with requests for a ‘Negro doll made of rubber.’”

Smith is quoted as saying he wanted to make dolls for all, “not just white children.”

But he waited to produce one associated with a racist radio show? Okay. . .

As with Sara Lee, the doll’s design was based on photographs of Black children, this time from Harlem. Production of the doll was 12,000 dolls daily for several weeks. While some advertising described Amosandra as “exquisitely molded” and the “chubby baby from Amos ‘n Andy fame,” some called her a “cute pickaninny” and a “cunning bundle.” Ads for the doll which included pictures of the white radio stars who portrayed Amos ‘n Andy had them appearing as they did in public relation outings– wearing blackface.

There was the hope that race relations would change due to the doll, according to the news article. It cited an editorial that had appeared in the Beacon Journal at the doll’s production that stated, “Finding it natural for dark and white dolls to associate together, they may grow up with minds that are more open than their elders.”

Ebony magazine lauded the beauty of Amosandra, along with that of Sara Lee and Patty-Jo.

Patty-Jo was a doll based on a character by Jackie Orme, the first Black female cartoonist, from the Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger cartoon. The Terri Lee doll company manufactured Patty-Jo between 1947 and 1949. The doll came with a fashionable wardrobe, was “meant to capture the spunky, smart, precocious and cute personality of Ormes’ comic character,” Caitlin McGurk writes in an article on the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum webpage at Ohio State University.

The creation of Black dolls that mirrored authentic features of Black people and contradicted the stereotyped caricatured dolls were the goal of the companies above. Though they did not last, they provided a path. One that would lead to a doll born out of a revolution.

***

The 60s for Black Americans were a time of change. The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Arts Movement, and the Black Power Movement. Public Historian Yolanda Hester says a doll reflected the ideas of them.

She would be called ‘Baby Nancy.’

***

The doll, Hester says,” is significant to the Black community and also communities at large.”

Robert Hall and Lou Smith, both who had been members of Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), created the community organization–Operation Bootstrap– that would produce Baby Nancy through its toy company, Shindana Toys. Because of that, Baby Nancy ” reflected all those sort of dreams of equality and citizenship,” Hester says.

“When Baby Nancy was introduced to the marketplace in the late 60s, she was a big success. And, although there had been Black dolls that had been produced prior to Baby Nancy, they all kind of fell or faded away for a variety of reasons. This success was very significant. It made Baby Nancy a trailblazer in the marketplace. And, ultimately that success provided a blueprint for other companies . . . interested in producing ethnic dolls.”

Operation Bootstrap came as a response to the Watts Rebellion. Hester said a lesser-known story about Shindana Toys is that the people who worked at the company were from the community. The toy factory was “right in the heart of Central LA.”

“So while it was blazing a trail nationally, and providing parents who had trouble finding a Black doll. . some hope, it was also supporting this community in Los Angeles.”

Mattel was instrumental in the creation of Shindana Toys, providing capital, machines, and training.

Historian Rob Goldberg, author of Radical Play: Revolutionizing Children’s Toys in 1960s and 1970s America, says Shindana approached the making of Baby Nancy in a new way.

He says, “What they did was something that no other company had ever done before, as far as I know. The research and development department created a local contest and invited local schools to have children actually draw what they saw as a positive portrait of a black child.”

The final version was a composite of what the children had submitted and a version of Shindana’s research and development department.

A second thing Shindana did was to give a version of Baby Nancy hair that had been heated up in a oven shipped from Italy that created a certain texture. In toy history, Baby Nancy was the first doll to have an Afro.

Goldberg says that the commentary on Shindana’s work was positive at the time because the company had done something new in terms of trying to represent Blackness in dolls and in a way that celebrated it.

“That was telling Black kids that they’re part of this world of childhood that’s represented in the toy business,” Goldberg says.

“More and more companies began to make so-called ethnically-correct Black dolls by which they meant Black dolls that were uniquely sculpted to reflected the associated physical features of people of African descent and by doing so, by making these new ethically-correct dolls, Shindana led the way. All the major companies in the industry followed.

“And what happened was, it really invited, for the first time, Black children into this world of children’s play and children’s culture that they’d always been excluded from because they hadn’t been represented.”

Shindana is Swahili for competitor.

Baby Nancy was inducted into the Toy Hall of Fame in 2020.

Baby Nancy

Photo Credits

Baby Nancy — Debbie Behan Garrett

Dapper Dan –Mebane Antique Auction Gallery

The Doll Test, National Park Service|

All others–Gwendolyn Mintz

Other Media

Baby Nancy Induction Ceremony, courtesy of The Strong National Museum of Play (with thanks to Mary Missall)

Berry & Ross ad, courtesy of The New York Public Library

Santa Claus letter, courtesy of Metro Nashville Archive

Links:

Black Dolls Matter

Corage Dolls

Herstory Doll

Pretty Brown Girls

Step Stitches

Trinity Designs